ROGER UNDERWOOD

COMMENT

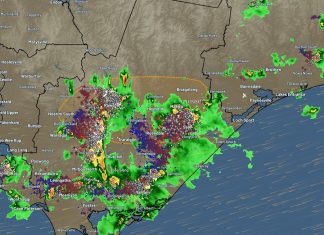

By ROGER UNDERWOOD RECENT multi-million-hectare forest fires in Canada have again highlighted the dichotomy of opinion within the Australian community when it comes to bushfires. The knee-jerk response from environmentalists and most academics has been “it’s all due to climate change”. Fire scientists and bushfire operational people on the other hand, many of whom are in contact with Canadian land and bushfire managers, draw an entirely different conclusion: irrespective of the cause of the ignitions, the explanation why the fires have been so difficult to control and have done so much damage is basically the absence of sound land management – in this instance, the failure by Canadian authorities to prepare potential fire grounds in the expectation of fire. The reports my colleagues and I have received from young Western Australian men and women deployed as firefighters in Canada have been especially revealing. They recount how they have been fighting fires in forests that have been logged and then abandoned, and of forests left long-unburnt, carrying tonnes of flammable fuel. And they have been struck by three things: (i) the enormity of the resources that are brought to bear on firefighting in North America but which are still unable to control the fires; (ii) the futility of attempting to control fierce forest fires with aerial water and retardant dropping; and (iii) the difficulties in construction of fire containment lines in forests growing on thin, mossy soils overlaying permafrost; bulldozers become bogged, or worse, disappear into sinkholes. “Would it not have been better to do some fuel-reduction burning in these areas, so that tracking the edge of wildfires with bulldozers and trying to extinguish them with water bombing would not be necessary?” is a question on the lips of many experienced Australian bushfire specialists as they contemplate the Canadian disaster. The dichotomy of views about the bushfires (climate change versus ineffective land management) has an echo in the other great bushfire controversy in which Australia is mired: what is the best approach for dealing with the bushfire threat? One group (mostly academics and environmentalists, supported by retired “fire chiefs” ready for their closeups) opts for Emergency Response (sometimes known as “the American Approach”) – wait for a fire to start and then throw everything at it so that it is extinguished before it does any damage. The alternative approach (mostly promoted by bushfire practitioners and at one time known as “The Australian Approach”) accepts that an emergency response will always be needed since bushfires can never be prevented, but adds that if the fire grounds are properly prepared in expectation of a fire, then fires will be easier, cheaper and safer to control by emergency responders. The chief mitigation tool of the second group is fuel-reduction burning – deliberate, supervised burning under mild weather conditions. The aim is not to “prevent” bushfires, which is impossible, but to reduce the amount of flammable fuel in bushfire-prone bushland in advance of a bushfire starting. It is combustible fuel, comprising dry leaves, twigs and flammable shrubs that feeds bushfire intensity; and it is bushfire intensity that determines how hard, dangerous and costly a fire is to control. Mostly this argument has been one-sided in recent times. The Emergency Response proponents are well in control of bushfire management in Qld, NSW, and Victoria. In these jurisdictions, bushfire mitigation is either not properly funded or is not carried out in a way to ensure it will be effective in wildfire control. Fuel-reduction burning is condemned because, its opponents assert, (a) it causes ecological and environmental damage; and (b) it does not help in the control of bushfires. A more recent addition to the armory of the anti-burners is the preposterous idea (dreamed up by a Curtin University academic) that if eucalypt forests are left long-unburnt they become non-flammable. Incredibly, this nonsense has been embraced by urban environmentalists and is constantly being pushed at the public by a compliant, incurious and all too gullible media. Those who advocate the Emergency Response Only approach are promoting an out-dated, failed and a failing strategy. Nowhere in bushfire-prone areas anywhere in the world has this approach worked. It failed in south-west Western Australia, culminating in the 1961 fires; it failed in south-eastern Australia, culminating in the devastating Black Saturday and Black Summer fires, and it is failing (again) as we speak in Canada and the US, where astronomical resources (by our standards) can be thrown at bushfires. It will inevitably fail again in eastern Australia sometime in the next few years as bushfire fuels build-up again in the areas burned in Black Summer and nothing is done to reduce them.None of the arguments against prescribed burning stack up in the face either of science or experience. On the contrary. Biodiversity and the environment are altogether better protected by mild controlled fires than by intense uncontrolled wildfires. There is not an experienced firefighter anywhere in the world who does not understand that it is easier, safer and cheaper to control bushfires in light rather than in heavy fuels. Far from becoming non-flammable, karri forest left unburnt for nearly a century carries massive tonnages of combustible fuels. Unfortunately, this experience does not trump the ideology of the green academics and activists who are calling the shots on bushfire policy in Australia’s eastern states. This depressing situation is leading many bushfire specialists of my generation to consider slashing their wrists in despair. “Let the bastards burn, if that’s the way they want to play it” is a comment I heard from one of Australia’s most distinguished bushfire scientists, sick to the core of the way the authorities in Victoria and NSW are deliberately setting up rural people and environments for destruction. I am frequently asked if I can explain the madness of governments and professional bureaucracies who promote a failed and failing bushfire strategy, and who blatantly ignore the lessons of history. I cannot explain it. The only thing I can do is to relate the good news story from Western Australia, one corner of the continent where there is a firm commitment by government to invest in effective preparedness and mitigation as well as in emergency response. The WA approach is not perfect, but it is thought-through and supported by good science. The hearts and minds of our political leaders and our professional bushfire managers are in the right place. The consequences of action, and of inaction, are understood. The bushfire authorities accept that they are accountable for bushfire outcomes. AUSTRALIA is in the depths of an era of incompetent and failing bushfire management. The approach adopted by governments and land and fire agencies (in NSW and Victoria, in particular) is deeply unprofessional, and will inevitably result in new bushfire disasters in the years ahead. To rely on Emergency Response is to rely on something that can never work when needed most, i.e., when there are multiple ignitions in heavy fuels on a day of extreme fire weather, at the end of a drought. This is not an imaginary scenario, but a set of probabilities that will occur once or twice nearly every few summers, somewhere in the country. Needless to say, when the next cycle of nasty fires occur in Australia the cry will go up “it’s all due to climate change”, but I am not sure how long this excuse for incompetence can be sustained. Eventually someone will want to see actual evidence of how the climate has changed to produce such dramatically horrible outcomes. For another, people will want to know why climate change has not caused similar disasters in Western Australia. Furthermore, every bushfire scientist and manager in the land must know about “the bushfire behaviour triangle” which demonstrates that (once you have ignition) the behaviour of a fire is a product of weather, fuels and topography. The merest study of history will reveal that the Australian bushland has experienced droughts, severe fire weather and bushfires across millennia. Any increase in the frequency of severe fire weather due to climate change or climate cycles, regardless of the cause, can only be counteracted by focussing management effort on fuels. Nobody can control weather or alter topography. A final thought on the Canadian bushfires. One of the things which is most often criticised about fuel reduction burning is that it generates smoke, and it is claimed that this harms some people’s health and contributes to global warming. The smoke from the Canadian bushfires blanketed the entire north-east of the USA for weeks and has even reached Europe. Smoke is an inevitable consequence of fire, but the smoke from a mild-intensity prescribed burn is light and ephemeral and can be managed to minimise the risk of smoking out major population centres. The reverse is the case for smoke from wildfires, another key factor in support of programs that make wildfire control quicker and easier. This article is an abridged version of an opinion piece that appeared in Quadrant Online Roger Underwood, OAM, is a former district and regional forest manager in Western Australia and a specialist in bushfire operations, policy and history. He was for 20 years the Chairman of the Bushfire Front, an organisation dedicated to minimising bushfire damage in Western Australia.