By PHILIP HOPKINS

CUTTING greenhouse gas emissions to fight climate change requires nuclear energy and is impossible with just wind and solar.

That was a key message by nuclear expert Robert Parker to a meeting in the Morwell RSL on Wednesday, September 18 attended by around 150 people. Mr Parker, a civil engineer with a Master of Nuclear Science, is a former president of the Australian Nuclear Association.

Mr Parker said the current system was difficult to manage and expensive to operate.

“Wind, solar and storage are fraught with problems. No nation on the planet has been able to achieve total energy supply using solar and wind. What has worked historically – base load power stabilises power and communities and provides long-term jobs, but is associated with greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

In contrast, France “produces massive amounts of electricity with nuclear” and had power vastly cheaper than non-nuclear Germany.

Mr Parker, who accepts human-driven global warming, said splitting the atom in a nuclear reactor produces lots of energy – 200 million electron volts compared to an atom of carbon in coal of about 10 electron volts.

“The difference is 20 million fold. Using this process gives rise to massive energy density and a very sustainable low footprint energy source,” he said.

Mr Parker said a 2021 report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, ‘Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity Generation Options’, had shown that nuclear was safe and sustainable. The report showed that coal had high emissions and natural gas was relatively high.

“Wind and solar also have embodied emissions because this is a life cycle analysis and includes diesel and coal that go into the manufacture,” he said.

In terms of average grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hours of electricity, wind was 12g CO2/kWh and solar was 32g CO2/kWh.

“The lowest emitting energy source of the lot – the ‘greenest’ – was nuclear at 5-6 grams of CO2,” he said.

The report looked at the materials intensity of the different clean electricity generation technologies, including uranium, over an 80-year period. Tonnes of materials were needed to create the system. A 100 per cent penetration by renewables amounted to 380 million tonnes of materials – more than 200 million tonnes for wind and more than 80 million tonnes for solar PV – with 191 million tonnes initially.

In contrast, the initial nuclear option required 49 million tonnes and then 72 million tonnes at 80 years.

“One hundred per cent renewables use 3.9 to 5.3 times more materials than the optimum nuclear solution,” he said.

“It’s possible to recycle renewables, but not the concrete foundations of a wind terminal. It is impossible to fully decarbonise with wind and solar as embodied emissions make that impossible.”

Mr Parker said the UN Commission for Europe report also demolished the idea that nuclear causes cancer. Nuclear came second after hydro. Coal rated high, but “Australian coal has a much better coal record than others around the world”.

The UN wrapped up all these conclusions taking into account normalised, weighted and environmental impacts from the various factors – toxicity, the oceans, particulates, climate change. Small hydro performed the best, followed by nuclear, with fossil fuels high on the list, while renewables were better. The conclusion: “Nuclear has no case to answer in terms of sustainability.”

Mr Parker said seismicity had emerged as an issue due to earthquakes in the Hunter Valley and “Gippsland has a few fault lines near Morwell”. Mr Parker approached an expert in the US on seismic activity and nuclear.

“Professor Andrew Whittaker is a Melbourne boy with an undergraduate degree at Melbourne University. He’s a Masters and PhD from Berkley University and now sits on the White House Group on New Nuclear. He chairs and sits on code-writing for seismicity on the adaption of nuclear in the US, and writes the code that goes into the nuclear energy division of the US Department of Energy,” Mr Parker said.

Professor Whittaker said seismicity in Australia was similar to that in Central and Eastern United States – far from plate boundaries in central and eastern US where there are 87 operating reactors in 51 sites in 25 states.

Using standard US and international practice, Professor Whittaker concluded: “If AP1000 (standard nuclear plant) in the Latrobe Valley, ground shaking with return period (RP) of 50,000 years used for design, no damage accepted. Contrast with other infrastructure, RP equals 500 years and significant damage accepted.”

“Latrobe Valley poses no siting problem for AP1000 and advanced reactors: earthquakes, floods, bushfires, extreme winds. Expectation is safe construction and operation of nuclear power plants, even under very rare, extreme natural hazards identical to operating plants in the US.”

Mr Parker said it was important to get Professor Whittaker’s words quite clearly.

“There is no issue in Gippsland with building a nuclear power plant,” he said.

There were several nuclear plant possibilities, including AP1000, which would be ideal for Latrobe.

“There are small nuclear power plants of 300MW, however, you have the population, the grid connection, so it would be a shame to waste it,” he said.

Smaller plants were better for regional Australia. Internationally, “four are being built, one in Ontario, and in Canada, the first of them is due to be commissioned in 2029”.

“They are doing the foundations as we speak. They are passively cooled reactors,” he said.

How close can nuclear be built to populations?

Mr Parker referred to Pickering, Canada, where populations groups lived four kilometres, 1km and 2.9km. from a nuclear power station.

“The populations are still quite close. There’s an exclusion zone – people don’t live there – that’s the real estate, where the fence is located. It has nothing to do with a danger zone; the owner has total control over what happens,” he said.

Outside of that was a ‘low population zone’, where typically in a US nuclear community, 500 people per square mile, (200 per square km) lived within that zone. An ’emergency zone’ was where people “become notified in the unlikely event something should happen” – do they leave the area, do they remain in place or do nothing.

“There are different plans depending on the distance from the zone,” he said.

Mr Parker said the Coalition had released a nuclear plan for seven sites in Australia, including the Latrobe Valley.

“It’s not an aggressive policy; they have to balance the position with the entire electorate,” he said.

In the current situation, as demand grows with transport and electric vehicles, an increasing amount of electricity is needed.

“By 2060, it could be 360TWh compared to the current 200. That’s a contested number, it’s hard to predict,” he said, but the lifecycle analysis showed that with nuclear the CO2 emissions intensity would rapidly drop in the years to 2060.

“Canada built 18 reactors in 18 years, the French built 58 in 22 years to put 63GW on the grid. Here we are talking about 36.8GW, a lot less than the French did.”

Mr Parker said the cost in Australia to build reactors was on average about $13 billion over a year and a peak of $18b per year, with 13,000 jobs per year in construction.

Nuclear was accused of being too slow, but people talked only about the first reactor, not the 10th or 20th.

“Nuclear systems are built on a fleet basis, the first is not relevant,” he said.

Mr Parker said a 2023 statistical review of World Energy report showed that hydro produced the fastest lowest carbon energy systems produced per capita, but also came with fearful environmental effects. However, seven of the 10 fastest non-hydro programs were all nuclear.

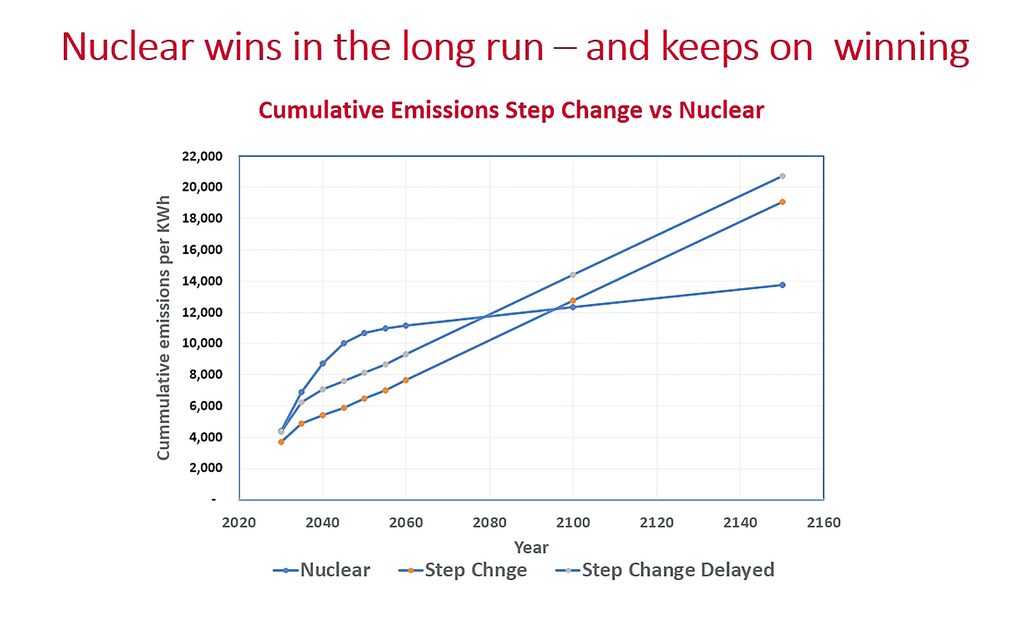

“AEMO’s Step Change scenario requires deployment of renewable energy nearly twice as fast as has been achieved by any location globally and still contains 107gr/CO2kwh,” he said.

“A nuclear program would be conservatively achievable similar to Belgium’s program and has four times lower emissions intensity at 27/g CO2’kWh.”

Mr Parker said Victoria could provide 22 per cent, 8-9GW of nuclear power.

“Latrobe could build four of the AP1000 reactors we talked about. They have about the same cooling demand of the coal plants. Seismicity is not an issue. You have the workforce and people who need work, transport availability, grid connection, no nearby high risk infrastructure, and access to ports, This is a project for a century, not 25 years,” he said.

Mr Parker said the anti-nuclear legislation should be removed with all urgency.

“The Step Change scenario and 100 per cent renewables can’t be built within a reasonable time frame,” he said.

“Nuclear energy is central to our lowest cost, proven ultra low carbon-emitting electricity system.”

The use of large and small nuclear plants “can be ensured by partnering with great friends in Canada, the USA, the UK and our friends in South Korea, a great trading partner”, he said.