By MARY ALDRED

COMMENT

By MARY ALDRED

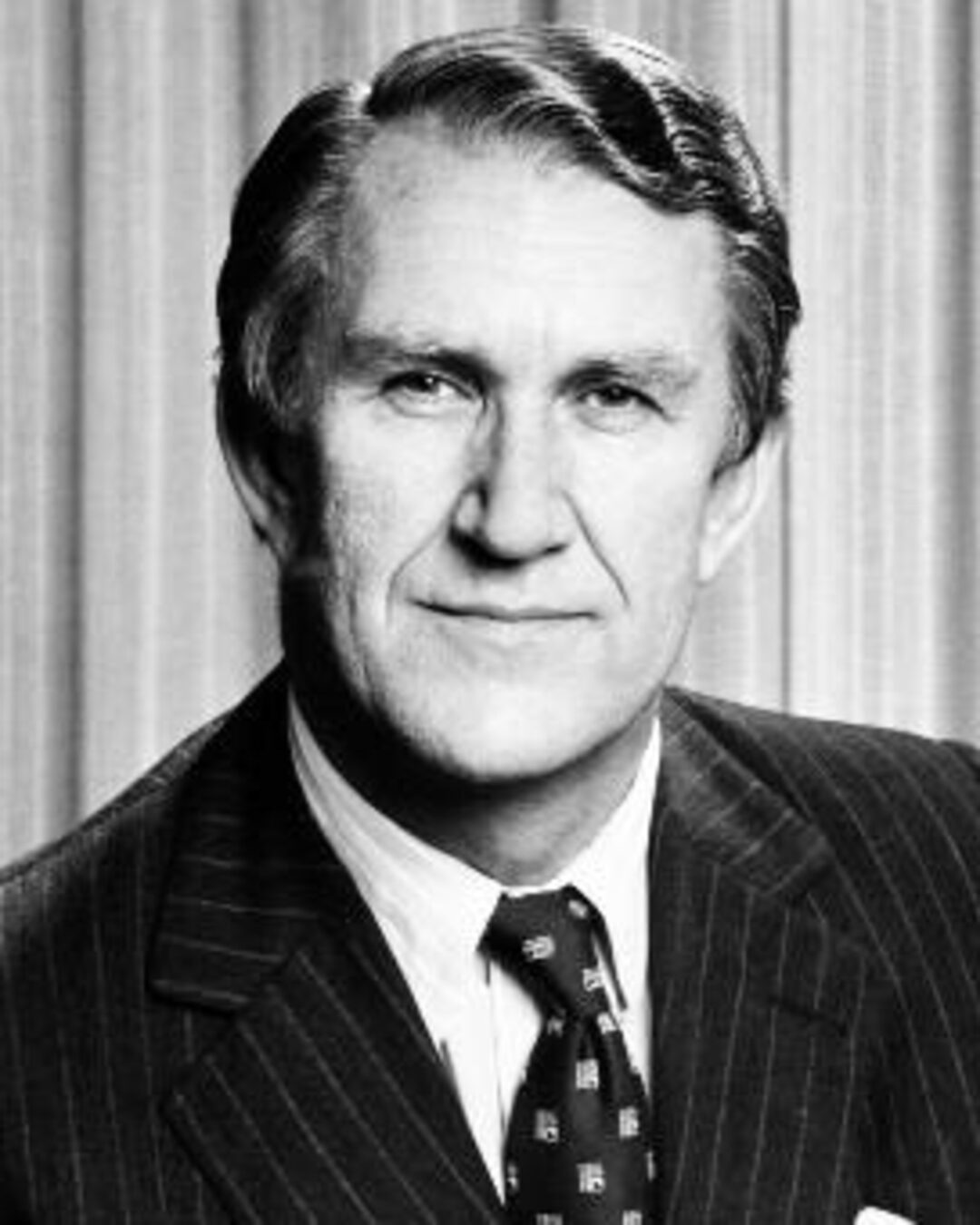

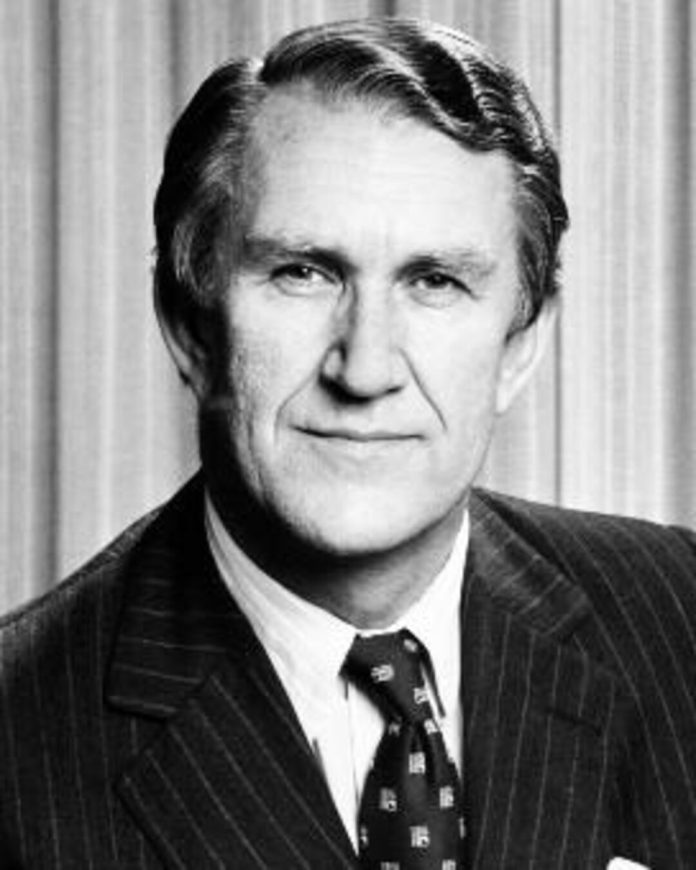

TUESDAY, November 11, 2025 marked the 50th anniversary of Malcolm Fraser’s appointment as Prime Minister following the dismissal of Gough Whitlam.

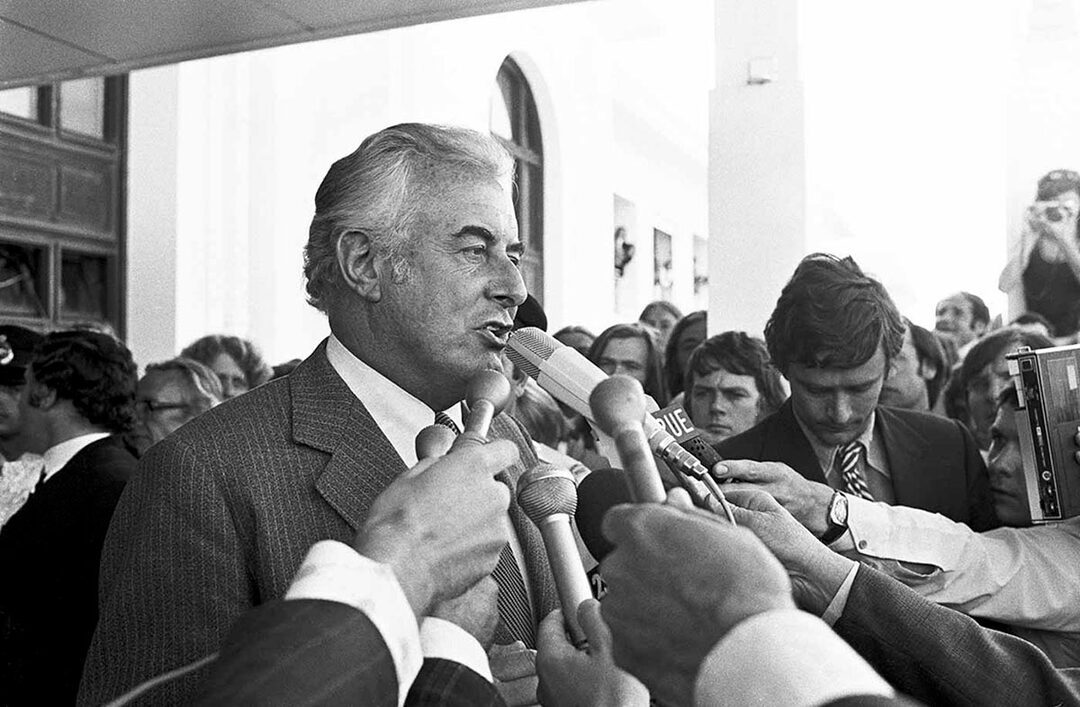

After 25 years of Liberal government, the momentum of Whitlam’s 1972 election win should’ve kept Labor in power for generations. But after less than three years, Labor’s lack of experience in government and incompetence in implementing reform became quickly evident to the Australian public.

From rolling crises including the loans affair and ministerial misconduct – Whitlam’s was a bad government that had to go.

The man that would go on to be the country’s 22nd Prime Minister and the last Victorian Liberal to hold the office, entered the parliament at the age of 24.

It is hard to imagine anyone presenting a fully formed sense of self at that age, but Fraser brought with him a vision for how liberalism could transform Australian lives.

Fraser was a classical Liberal, with a focus on individual freedom. He was especially concerned about the type of socialist overreach he’d seen first-hand while studying at Oxford during Clement Atlee’s Labour government in Britain.

Countering the threat of socialism to the Australian way of life inspired his early political activism.

Fraser became a Minister in the Holt government, which was instrumental in the dismantling of the White Australia policy. Throughout his prime ministership, Fraser was strident in pursuing anti-racist polices and multicultural reform. He progressed social reforms at a pace Australians were more relaxed and comfortable with.

As a Defence Minister, he modernised the military and saw the US alliance as critical to protecting Australia and the world from the threat of communism. He was underwhelmed by US Jimmy Carter’s limited deterrence of Russia, instead ensuring that Australia resisted Soviet expansion into the Pacific. Working with his foreign minister, Andrew Peacock, he was instrumental in developing a more self-reliant Australian strategic posture.

Across social reform, Fraser doubled funding for women’s shelters overnight and established the Special Broadcasting Service, the offices of youth affairs and child care, established the National Women’s Advisory Council and granted the Northern Territory self-government and initiated the first native title.

On the environment, his government banned whaling, instituted the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, and placed five areas on the World Heritage List: the Barrier Reef, Kakadu, Wilandra Lakes, Lord Howe Island and South West Tasmania.

The father of modern-day multiculturalism, he championed a compassionate approach to humanitarian migration, welcoming Vietnamese refugees fleeing communist persecution.

Fraser envisaged a role for Australian leadership outside our immediate region as well, with his government a champion on countering South African Apartheid and promoting greater inclusion and respect for the self-determination of African nations.

One of Fraser’s underrated achievements was economic reform. Craig Emerson noted that Whitlam was not much interested in economics – and it showed. Fuelled by Whitlam’s unrestrained social spending programs, real government spending increased 20 per cent in one year, followed by a further 16 per cent the next year.

Owing to the economic recklessness and administrative incompetence of the Whitlam government, Fraser did not inherit a healthy economy. Australia suffered from an economic downturn influenced by international events and exploding wage rates, particularly in the metals industry. Fraser sought to apply greater spending restraint, foregrounding the economic reform of the Hawke and Keating years.

The transition from Whitlam to Fraser was emblematic of what has become a recurrent political pattern: a disastrous Labor spending spree followed by Liberals coming into office to restrain excesses and right the ship. Like Whitlam before him, Anthony Albanese seems bent on keeping up the tradition.

Fraser was careful in dealing with the human consequences of the recession and unemployment caused by the Whitlam government. Fraser’s adviser, David Kemp, later a senior Howard government Cabinet Minister, describes Fraser’s as a transitional government: rescuing Australia from the reckless excesses of the Whitlam government, and preparing the nation for more open, free trade economic reforms later implemented during the Hawke and Keating years.

In bringing expenditure under control in his first two budgets, Fraser showed that significant economic rehabilitation in a short period was possible.

Fraser’s economic tendencies were an extension of how he saw the Liberal Party, and liberalism. Fraser very much saw the role of politics as fostering conditions that the individual could thrive in and for this a degree of limited intervention was required

I asked Kemp recently what he saw as the crowning achievements of the Fraser government. Without hesitation he replied that it was the defeat of the Whitlam government, which had to go, and the reinstatement of a Liberal government, fundamentally driven by Menzian principles. Fraser opened the door to debate on how far those principles would extend to economic management.

Kemp describes Fraser’s concept of liberalism as focused on the rights and freedoms of the individual and grounded in that idea that a good society had to be based on the dignity of every human being.

Fraser’s pragmatic approach to governing was shaped by his Presbyterian upbringing in Victoria’s western farming district. He is known for quoting from the play Methuselah, where the old man says to the boy “life wasn’t meant to be easy”.

But few would remember the line that follows, where the old man adds “but, my child it can be delightful”.

While many see that first fragment as an analogy to Fraser’s stoic outlook, the second half of the quote encapsulates that Fraser was in fact also a great optimist towards humanity, and especially about Australia.

As modern-day Liberals once again build an agenda to replace another disastrous Labor government, we would do well to place Fraser’s brand of stoic optimism at the core of our outlook.

Mary Aldred is the federal Liberal Member for Monash