It is one of the cruel ironies of history that sometimes the importance of major events goes unrealised until it is too late to change the outcome.

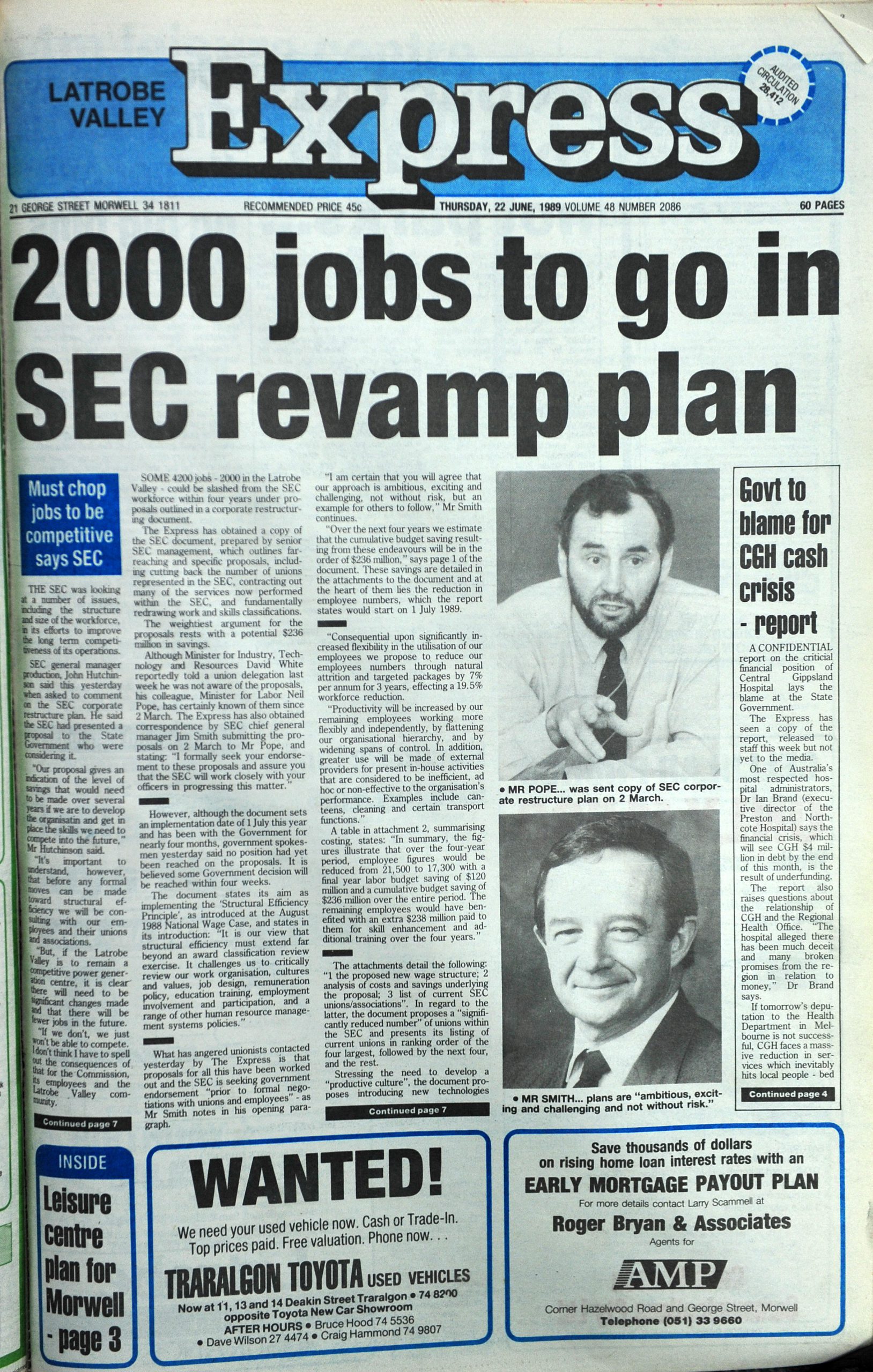

And so it was on Thursday, 22 June 1989 when members of the Latrobe Valley community arrived home from work to retrieve copies of The Express from their letterboxes.

That day the newspaper carried a headline which heralded the beginning of the SEC corporatisation and the shift from a thriving community to one where unemployment, empty shops and all manner of social problems would become part of every day life.

The headline that day – ‘2000 jobs to go in SEC revamp plan’ – was shocking enough but the story itself wasn’t alarmist.

Instead, the story struck a more measured tone with readers presented with a straight report in which SEC general manager production John Hutchinson outlined how job losses were vital to securing the organisation’s future.

“If the Latrobe Valley is to remain a competitive power generation centre, it is clear there will need to be significant changes made and that there will be fewer jobs in the future,” Mr Hutchinson said.

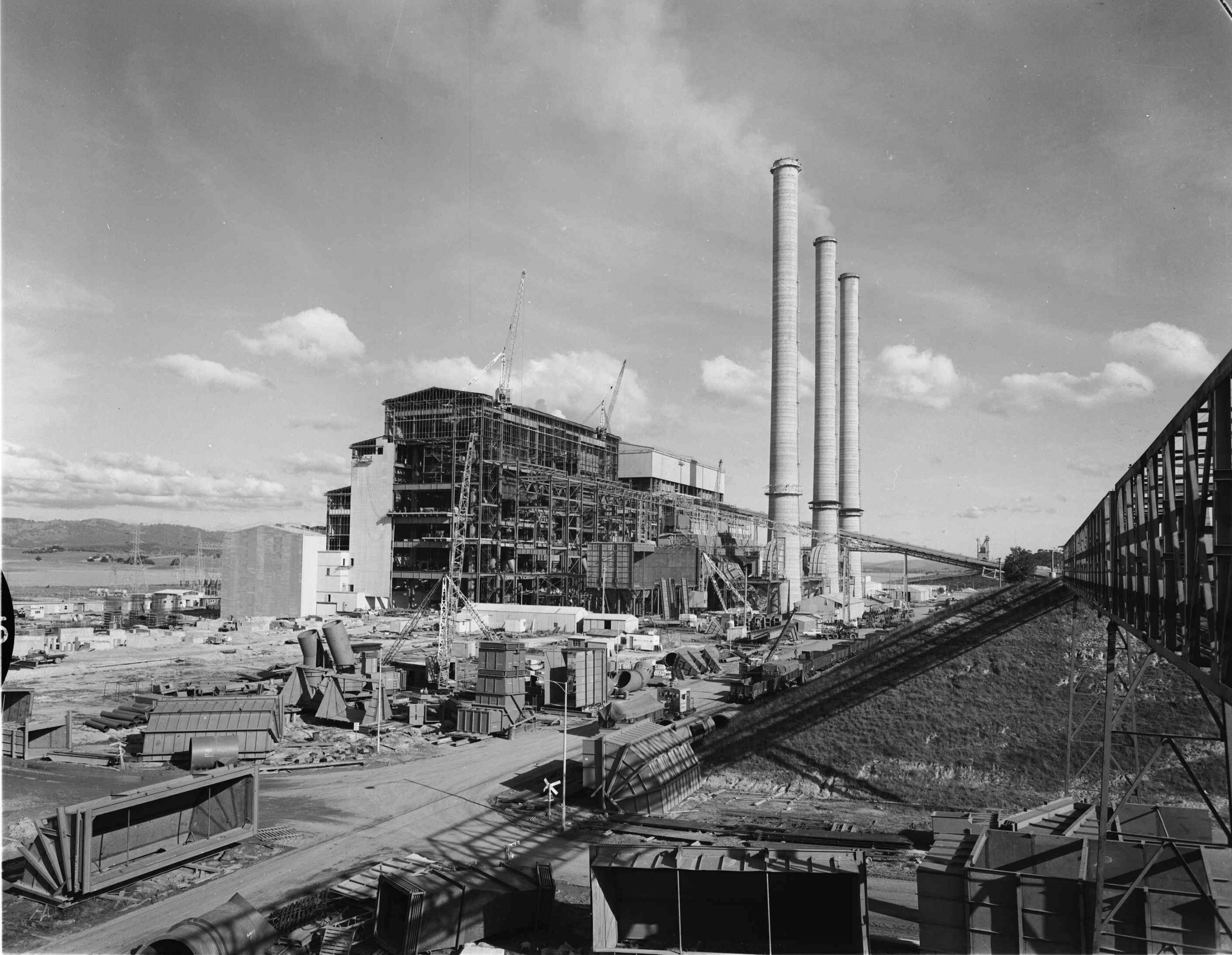

With that, a process began which would eventually result in thousands of job losses and the eventual privatisation of the region’s power stations after Jeff Kennett became premier at the 1992 state election.

Former Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union mining and energy vice-president Graeme Middlemiss said the 1989 restructure – or corporatisation – of the industry was designed to make the SEC “lean and saleable”.

“So the SEC set about to lose what they considered fat,” Mr Middlemiss said.

“They considered these people fat, or excess, and they set about cutting the workforce right down to the point where somebody would buy it as is and the real tragedy, the real job losses occurred in corporatisation.”

The SEC’s restructure report, which was obtained by The Express at the time, outlined how 4200 jobs would be slashed across the corporation within three years which would deliver $236 million in savings.

Two thousand of those jobs would be lost in the Valley, delivering a 19.5 per cent reduction in the workforce across the corporation, with the cuts to be achieved by a mixture of natural attrition and voluntary redundancy packages.

By September the following year the first workers began receiving redundancy offers and the most popular conversation topic in the Valley became discussions about who had “taken the package”.

Former CFMEU mining and energy division president Luke van der Meulen, who in those days was involved in the union’s forerunner, FEDFA, said the offer of voluntary redundancy sparked an exodus from the SEC.

“We could have stood at the gates and stood there and said ‘don’t leave’ (without it having any effect) – they were rushing,” Mr van der Meulen said.

“Instead of 20 per cent going out, it soon got to 30, 35 (per cent).”

The result was chaos within the organisation.

One day someone would be manning a machine or overseeing rosters and the next they’d be gone.

“They just disappeared overnight,” Mr van der Meulen said.

“So we had to really have a real struggle negotiating with the employers across the three sites about who was going to do what; our structures started collapsing.

“Then we really started putting some real detail into getting staffing structures, classification structures and we fought really hard for those.”

In those days the package was two weeks’ pay for each year of service.

There was more internal upheaval inside Hazelwood and the other generators, with moves towards union rationalisation which would force workers to join one of two unions – the Electrical Trades Union or the Australian Services Union.

The problem was the ASU was perceived as the “bosses’ union” while the ETU was seen as a niche group, Mr van der Meulen said.

Although the move was resisted, former Hazelwood unit attendant Adrian Ellison remembers management trying to exploit divisions in the control room between FEDFA, which opposed the restructure, and the ASU which backed it.

One incident occurred inside Hazelwood after ASU and FEDFA control room workers were moved onto different industrial awards and the issuing of what Mr Ellison called “the blackmail letter”.

He said the station superintendent at the time granted a pay rise to members of the ASU but not to FEDFA, despite the workers doing the same work.

“Then he wrote a letter to everybody in the FEDFA and said, ‘well, if you want a pay rise join the ASU’, and that was called the blackmail document,” he said.

“That caused an absolute furore within the operations group.”

But despite those tensions, they still had jobs.

The situation was much harder for those workers across the various stations the SEC wanted out but refused to take the package.

They found themselves placed in what became known as ‘veggie patches’ – rooms at the various sites where the workers were left to sit with no work until they eventually cracked and accepted redundancy.

While Mr Middlemiss did not witness Hazelwood’s ‘veggie patch’, he remembers its impact at Loy Yang A.

“They were bullied out (of) those veggie patches as they called them,” he said.

“I know at Loy Yang the manager would come in every Monday and say to them ‘you’ve probably only got a fortnight guys, I can’t guarantee you the package. If you sign here we’ll give you the package’. “And every fortnight they’d get that pressure and a lot of them cracked.”

The impact on the community was devastating, with a script local residents remember too well – unemployment skyrocketed, housing prices crashed as people looked to get out and welfare dependency boomed.

“There are people still in the Valley who have just had a few casual jobs between the corporatisation/privatisation period and now,” Mr Middlemiss said.

“They reach retirement age effectively with the last 25 years of their career on the dole.”

There were some success stories, Moe businessman Brad Law used the opportunity presented by the package to move into private enterprise and has enjoyed a successful career since.

Mr Ellison took a package expecting Hazelwood to close and moved into a consultancy where he dealt with the newly unemployed.

“I came into contact with a lot of people who had taken the package and a lot of people who had taken the package, especially in ‘89 when it first hit, they were at the lower echelons of the skill base,” he said.

“I saw the result… over a period of four-five years I lost probably a dozen clients from suicide and I’ve held Kennett (the architect of privatisation) accountable for that ever since,” he said.

Things would eventually improve, but not before the Latrobe Valley had shed nine per cent of its 1991 population, according to a landmark 2001 report about privatisation from Monash University researcher Bob Birrell.

Now, with 750 Hazelwood workers about to lose their jobs, the views of those who experienced the shockwaves of the 1990s are mixed.

Mr Middlemiss said he was concerned about what would happen to the region unless new jobs were created.

“Unless we get a base of decent, well-paying jobs we will just meander along,” he said.

“I’m not at all confident at what I can see at the moment.”

But Mr van der Meulen pointed to the possibilities available to the region if it can secure access to regional fast rail.

“I’m a glass half-full person,” he said.

“I think if we get a fast train and then if we can get this (Hazelwood mine) rehab going, there’s a lot of money and a lot of jobs in that.

“What I will say is, on this occasion the Labor Government’s come down and put ($266 million) on the table.

“That’s miles more than the previous governments.”