By KATRINA BRANDON

AN EXPEDITION into the deep can be found at the Latrobe Regional Gallery.

Into the Deep, by artist Bridget Hillebrand, is on show at the local gallery, where visitors can plunge into a speculative deep-water zone.

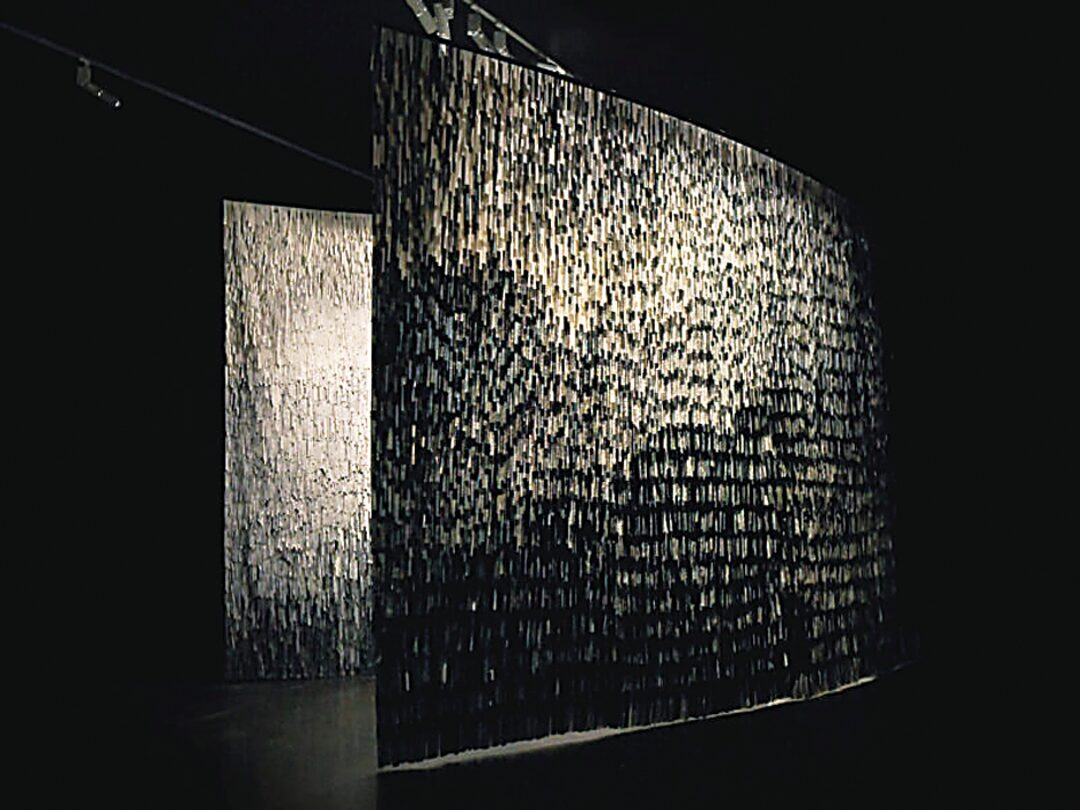

A step into the exhibit, where the dark encloses the spectator and the deep, cool sounds of the ocean flood ears. As the eyes of the audience get used to the room, the work – a 12 metre display from the roof to the floor, appears before their eyes in a black and white form.

Working in collaboration and partnership of work and viewer, movement around the piece moves like waves, with different intensity depending on the flow given by the audience.

Last month, locals were invited to ask questions about Ms Hillebrand’s work.

“I was approached by the gallery a few years ago to create a series of works for this space,” Ms Hillebrand told the group.

“I was going to make this very large work in response to the deep oceans.

“Our planet is 70 per cent water, 90 per cent of that is deep oceans. That’s an enormous amount of ocean. Eighty per cent is unexplored, unmapped, unknown. It’s a vast amount of our ecology that we have no understanding of or even a concept of. What is there? What is here?

“The work is aimed to primarily think about that how things that are hidden from us and unseen and unmanned, how can we have a relationship with that?”

Bridget Hillebrand is a Naarm/Melbourne-based artist whose interdisciplinary practice is concerned with time, ecologies, embodiment and place, with a focus on material relations with natural waterways and coastal ecologies.

A seven-minute looped soundtrack by composer Erasmus Toscano was created in collaboration with Ms Hillebrand, to help give the illusion of the “deep blue”, with a boat-shaped piece made using linocut, silver leaf on washi paper, and organza to complete the vision.

Sounds captured by Toscano were created by getting a hydrophone recording, a microphone that you can place into the ocean.

Ms Hillebrand told the group, “The beautiful sounds you’re hearing, of course, from my collaboration with the composer Erasmus Toscano.

“He’s a young composer. He’s in his third year studying musical composition, and I was very fortunate to work with him, because Erasmus has an incredible ability to sense what you’re trying to say.

“I wanted the sounds to be suggestive. He makes these beautiful shifts in tone. It was through this process of understanding acoustics and sound, too, that I got into hydrophone recording, where you just have a microphone that you can place into the ocean. It picks up all the really incredible sounds that you can’t normally hear if you’re diving or if you’re scuba diving or snorkelling.”

Clicking noises were highlighted by Ms Hillebrand in the audio part of the piece, as she was mesmerised by them. She mentioned that the clicking came from shrimps and that while they don’t know what they are doing to make the sound, it is a constant in the deep blue.

Bringing on more ideas for future pieces, Ms Hillebrand said that she is looking at the possibility of using soundtracks in other works.

During the group discussion, audience members asked Ms Hillebrand questions about her work and gained a deeper understanding of the little pieces and the inspirations of the piece in front of them.

To complete the work, Ms Hillebrand described the creation of the piece as a repetitive process as she cut and printed different strips that varied in tone.

In total, Into the Deep took up to six months to complete.

Within those six months, many challenges arose during the process, which were discussed during the talk. Challenges like choosing the right material to create the work and then finding enough of it to make the piece were one of the things that Ms Hillebrand talked about.

“I bought it (the materials) just from my local store up the road,” she told the crowd.

“I liked the material as it was matte rather than sheen, so I went back to the store and asked for more. Unfortunately, the store didn’t have the amount I needed, so I spent quite a bit of time hunting down the exact organza.”

Working in a smaller space with different lighting, Ms Hillebrand was unsure what the final perspective would appear once installed in the gallery. What was once pieces of blue strips, became a spectrum of black to white pieces, and silver strips turned to gold due to the lighting in the room.

Lighting for the piece is only central to the work and not the room. One or two lights highlight the work as the rest of the room appears in the shadows.

One of the audience members asked Ms Hillebrand about the darkness and why certain lighting choices were made.

“It’s really interesting when I was making the work, these are all printed as blue blacks and blue greys. But of course, when you’re in a dark space, they read as grey,” she said.

“It takes about five minutes for your pupils to get used to the dark. Then, over 20 minutes or so, you’ll see about 90 per cent of what you can see in the dark. I love the idea that the more light allowed into your eyes, the more familiar you become with the work, and the more you get to explore. This is what we’re trying to do – it’s the unknown that scares us.

“I read a lot and I try to learn about what’s happening with our deep emotions in the ecology of the deep ocean. For me, swinging in the deep ocean is incredibly scary.”

Into the Deep runs until September 28.