By ZAIDA GLIBANOVIC

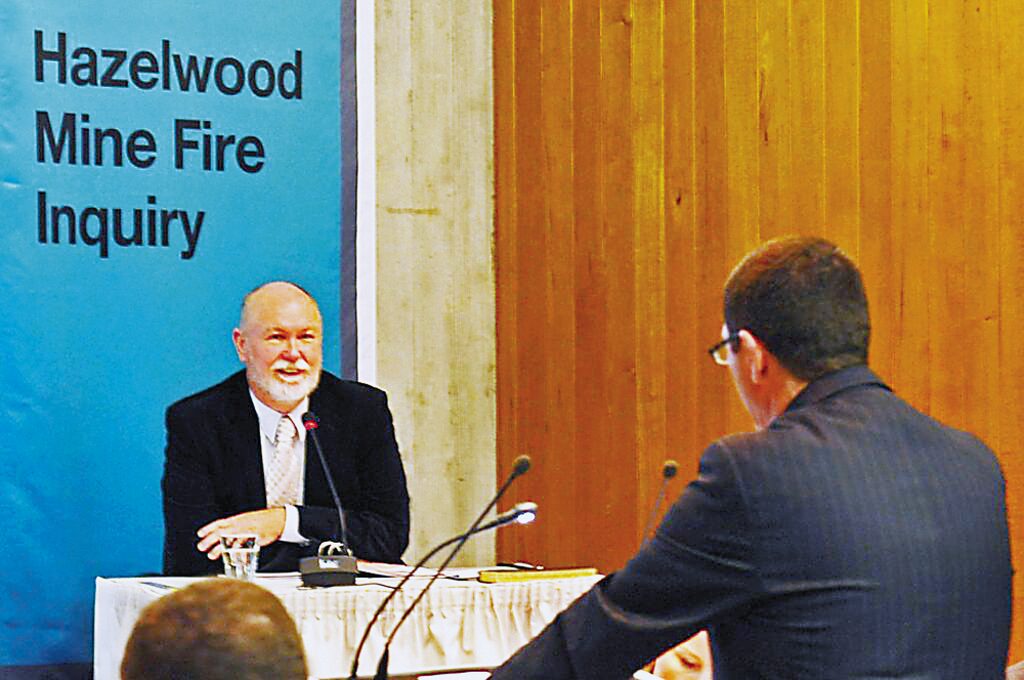

FRIDAY 9, 2024 – this Friday – marks the 10th anniversary of the Hazelwood Mine Fire, a disaster the region will never forget.

Ten years ago on that day, blistering heat and strong wind combined to create almighty infernos across Victoria in the summer of 2013/14.

One particular inferno burned for 45 days, suffocating Morwell and surrounding towns with smoke, causing widespread panic.

Burning only 400 metres away from some streets of the town, thousands of people fell sick within days as the dangerously toxic smoke entered airways. The people of Morwell were left with little direction from the state government as the smoke blanketed the town.

The Hazelwood open-cut mine fire was undoubtedly a disaster in many ways.

Beginning on February 9, 2014, the fire was among 70 other fire fronts being fought across the state.

The Hazelwood fire, in particular, started when embers from the multiple nearby grassfires reached the worked-out coal mine, feeding itself on the coal to create the worst mine fire in the history of the region.

Throughout the incident, 20 firemen received treatment for smoke inhalation, and at that time, there were complaints of serious health issues. The following health effects were reported: headaches, nausea, sore throats, diarrhoea, nose bleeds, painful eyes, chest discomfort, and exhaustion.

During the fire, many of Morwell’s day-care facilities and schools closed and moved their kids.

Hearing of the disaster, PhD candidate, Tom Doig, travelled to Morwell to witness the scenes with his own eyes.

He described the scene in his article for the New Matilda, Morwell Is ‘Like Mordor’.

“I bumped into Raku Pitt, who … had driven through Morwell that afternoon and was visibly shaken. He said it was ‘like Mordor’.

“There’s ash raining from the sky, a horrible stink in the air,” he told me.

“The coal mine fire’s going to burn for weeks, it’s right next to town and no one knows what’s in the smoke. People are wearing face masks, hiding in their houses – it’s like a zombie movie.”

“Small grey chunks of ash blew out of the sky like dirty anorexic snowflakes; it smelled like a bad barbecue.”

Sleeping at the Cedar Lodge motel in Morwell, Mr Doig recalled his terrible sleep, feeling as if he had “smoked half a packet of cigarettes”.

“I went to the bathroom and started coughing up bright green phlegm. Outside, the ash was thick on car bonnets and windshields. A Cedar Lodge employee was hosing off the plants in the garden. As one wit tweeted, “Morwell smells like a briquette broke wind”.

The Country Fire Authority (CFA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) seemed to be primarily concerned with minimising public alarm, rather than providing detailed information when the fire initially broke out.

Mr Doig has written two books on arguably Latrobe Valley’s biggest disaster.

Since his visit, Mr Doig has remained passionate about telling the Valley’s story.

Having released Coal Face and Hazelwood, Mr Doig’s research took him on unsettling journeys.

One of the most tragic cases from the entire episode was the story of volunteer mine fire fighter, David Briggs.

Mr Briggs worked through the night to try and stop the Hazelwood fire, oblivious to the danger to himself.

Mr Doig writes of Mr Briggs’ experience in his article for Meanjin, Ten years on from Hazelwood: last decade’s second-worst disaster*.

The twelve-hour night shifts, the fields of flaming coal stretching in all directions, the burning crevasses ten metres deep, the smoke billowing ceaselessly.

Steering the excavator across angry red crumbling ground, rivulets of ash running down the windows, staining the console in front of him. Coming home black-faced with soot, his work clothes soon ruined. Then, months later, feeling short of breath, ‘headachey’, weak. Vomiting. Collapsing. Passing out. David’s lungs, it turned out, were also ruined.

So was his life.

He told me what it was like to have terminal pulmonary fibrosis: to be able to hear, as he lay in bed trying to sleep, the alveoli in his lungs scarring over, stopping him from breathing.

Mr Briggs took legal action, winning the case against WorkCover despite their appeal efforts. Paid out in a lump sum, Mr Briggs was taxed harshly and in the end, he and his partner Penny Linegar were left with almost nothing.

Living on oxygen tanks with 18 per cent lung capacity, Mr Briggs was among the many victims who continue to suffer a decade onwards from the Hazelwood Mine Fire tragedy.

The EPA and the Department of Health were the key agencies responsible for informing the community about the smoke and ash produced by the mine fire and possible adverse health effects.

For local mother Wendy Farmer, the Hazelwood mine fire was a turning point in her life.

“It was a hot day, and it was a really windy day; we already had fires across the Latrobe Valley,” she said.

“We were already on edge.”

Ms Farmer recalled the dishes she was washing at the exact moment she received a call informing her that her husband Brett was immediately required at work at Hazelwood Power Station.

“It looks like hell,” is what Wendy’s husband told her when he reported back.

As the smoke began to thicken and air quality worsened, Ms Farmer grew concerned with the lack of health advice.

As the Latrobe Valley grew frustrated, Ms Farmer stood up and voiced her worries to the rest of the community.

The first protest that Ms Farmer attended was called ‘Disaster In The Valley – Dying For Help’, where people gathered to express their frustration at the whole situation.

Their frustration was with the mine owners, GDF SUEZ Energy International’s failure to rehabilitate the unused section of the mine or have sufficient safety measures in place.

Frustration also lay with the EPA and their slow reaction to address pollution concerns.

Ms Farmer wasn’t much of a public speaker, but as the panic set in she jumped upon the stage ready to champion the concerns of the community.

From that protest, Ms Farmer’s Voices of the Valley community organisation, was born to speak for those suffering from the hazard effects of the Hazelwood open-cut mine.

The last Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry found that the health response ultimately failed – it was given out many weeks too late following some of the most dangerous levels of air pollution.

As Morwell was inundated with ash and smoke, Victoria’s Chief Health Officer, Rosemary Lester, advised vulnerable residents in southern Morwell to leave almost three weeks after the fire started when initial instructions were to stay home.

Businesses in Morwell shut down as people were encouraged to stay indoors – Morwell became a ghost town as the fire burned.

Peter Rennie’s Rennie Property Sales worked behind closed doors and recalled the “terrible” conditions.

“With the fire there was like a stigma on the area – people weren’t coming because they weren’t sure what to expect – there was so much smoke and new people weren’t coming,” he said.

“It certainly made some businesses shut down and I know that there were government grants at the time to keep business going … but they probably weren’t enough for some.”

While the fire was officially declared ‘under control’ on March 25, 2014, it was not fully extinguished until June 6, 2014.

An inquiry was launched in August 2014, and found that GDF Suez was at fault for not reviewing or updating its fire preparedness and mitigation plan. Changing its name to Engie, the French multinational corporation went on trial in front of a Supreme Court jury and was found guilty of putting workers and the community at risk in June 2020, six years after the fire.

The Hazelwood Power Corporation (Engie) neglected to cut the vegetation surrounding the mine, failed to establish a suitable reticulated water system, failed to evaluate the fire danger enough, and delayed wetting down the surrounding regions.

The jury also concluded that Engie had not sufficiently evaluated the risk of a fire spreading inside the mine and that there was insufficiently skilled personnel on-site to put out the fire.

The court handed the Hazelwood Power Corporation a $1.56 million fine for those occupational health and safety breaches.

The Hazelwood Power Corporation was fined an additional $380,000, totalling over $1.9 million in fines for their fault in the blaze that caused $100 million in damages.

The power station once supplied 20 per cent of Victoria’s electricity, but was the power station with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in Australia when it ceased operations in March 2017.

CFA volunteer firefighter Doug Steley from Heyfield recalled working through the night trying to fight the fire – except the CFA had no water to fight the fire with because the mine owners had removed the water pipes.

In his account to the inquiry, Mr Steley described an unorganised and chaotic response to the fire, relaying to the investigators the overgrown shrubbery in the mine, equipment faults and accessibility issues.

There were two inquiries into the Hazelwood mine fire. The first one received widespread backlash for not delving into the health effects of the disaster.

Following a community uproar led by the Voices of the Valley and a change of government, a new inquiry was commissioned, which looked into the adverse health effects of the fire and related deaths.

Ms Farmer was among the first to enquire about the deaths that occurred during the fire and shortly after. Her advocacy work led to a more holistic Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry, which found that the mine fire contributed to 13 extra deaths in the Latrobe Valley.

There has been much research conducted in regard to the mine-fire caused and related deaths, with one researcher predicting as many as 46 people or as low as two could have died as a result of the fire. One thing was for sure, thousands of locals fell ill from breathing in the toxic smoke and research continues to delve into the effects the fire did and will have.

Latrobe City Councillor, Tracie Lund was the coordinator of the Morwell Neighbourhood House and Learning Centre and appeared as a ‘community witness’ at the Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry.

Ms Lund knew there was something wrong with the smoke that Friday – her husband Simon had battled Black Saturday blazes in 2009, but there was something different about the ash that was coming from the direction of the open-cut mine.

Initially, Ms Lund was simply worried about the welfare of people on the Morwell Neighbourhood House’s database, but what she discovered continues to play in her mind today.

As details were released of the fire in the mine, Ms Lund checked in on people on her roll call. They reported asthma-like symptoms, sore throats, coughs, and trouble breathing.

The EPA had yet to recognise the immediate pollution issue and problems to health. It was Ms Lund’s initial records of Morwell’s health issues.

Ms Lund documented all her phone calls down with many people suffering similar ailments.

“Three residents on Airlie Bank Road had sore throats and coughing. One resident in Morwell … reported to me that their daughter was having major issues with asthma,” Ms Lund recalled.

National media had no grasp on the local experience, with the EPA and Health Department continuing to keep health concerns on the down low as ash and smoke continued to pollute the air.

While the Hazelwood mine fire was arguably one of the worst health disasters in the region (bar COVID-19), it was one of those events that pushed the community to band together and individuals to stand up for what was right.

Two housewives were at the front of that charge: Ms Lund and Ms Farmer, who were among some of the first people who led the advocacy and have centred the rest of their lives on bettering this community.

Ms Lund said the Hazelwood Mine Fire and subsequent community response signified a turning point for the Valley.

“It’s extraordinary the change that has occurred through community advocacy and community push back,” she said.

Looking back at the disaster 10 years on, it has undoubtedly left a trail of health effects, but it also ignited some positive changes in the Valley.

Following the Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry, the state government designated the Latrobe Valley as a Health Innovation Zone in 2016 to improve health outcomes in this region.

The formation of the Latrobe Health Assembly was a key component of the Health Innovation Zone and continues to be a mechanism for increased community engagement leading to health improvement and integration of services.

The Hazelwood Health Study led by independent researchers from across the country and commissioned by the Victorian Department of Health continues to study the long-term health effects of the event.

By 2022, all 246 recommendations of the Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry were deemed closed or complete.

These actions included:

- Improvements to public communication and warnings – including the development of the VicEmergency app;

- Enhanced smoke plume modelling and air quality monitoring, including the Latrobe Valley Air Monitoring network co-designed by EPA Victoria and the Latrobe Valley community;

- The establishment of the Latrobe Health Assembly and a series of initiatives to improve the health outcomes of the Latrobe Valley community, and;

- Significant increases to rehabilitation bonds ensuring that the cost of mine rehabilitation in the Latrobe Valley would be borne by the coal mine operators.

For many, the mine fire was a wakeup call – a push away from multi-billion dollar energy companies and colossal exposed mines, a push away from old energy as the Latrobe Valley undergoes its clean energy transition and mine rehabilitation.

Much has changed over the past 10 years, but that community mobilisation and those active voices from this region carried on.

The devastation from the fire will remain a significant part of the Latrobe Valley’s history, and the region will always remember.

*Tom Doig’s new article Ten years on from Hazelwood: last decade’s second-worst disaster will be published in the latest edition of Meanjin on March 15, 2024.