Nature can be a powerful force to overcome.

Yallourn Power Station owner operator EnergyAustralia was reminded only too well of this last year, when the re-direction of an entire waterway through the middle of its open cut, catastrophically failed.

The Morwell River Diversion breached after heavy rainfall in the early hours of 6 June 2012, sending billions of litres of water into the mine, crippling the power station’s generation capacity.

One year, and more than $150 million later, mine infrastructure is still months away from a full repair.

Last week, Yallourn mine manager Ron Mether took The Express on a tour through one of the most complex infrastructure rebuilds the country has ever seen.

“It doesn’t get much harder than this,” Ron said, as the four-wheel-drive tour progressed through the bottom of the dormant Township Mine, which became an inland lake in the month after the collapse.

High up the mine wall – the peak level watermark can be clearly seen, 16 metres above the current levels.

Recently-installed power lines run the length of the open cut floor – replacing a former electric fire service system sacrificed during the flooding (a pond positioned on high ground gravity-fed a back-up fire system, the station’s firefighting capacity was never lost).

Ron’s superior, EnergyAustralia group executive manager operations and construction Michael Hutchinson, accompanies the tour from the back seat, however Ron does most of the talking; he has directly overseen more than 150,000-plus man-hours put into the response and repair effort to date.

“People went through a range of emotions (when the river breached) – many were thinking they might lose their job, that there might not be a mine or a station anymore… but once we got through that first month, they could see there was light at the end of the tunnel,” Ron said.

Starting his extended tenure at Yallourn in 1974, Ron has worked in the mine itself since 1993, however the past 12 months have unquestionably been his most challenging.

Driving out of Township, up over sticky clay onto the diversion itself, the sheer scale of the operation becomes apparent.

At the southern end of the diversion, a banked levee plugs the Morwell River, redirecting flows through a 3.6 kilometre (1.6 metre diameter) pipeline directly to the water’s intended destination – the Latrobe River.

Driving north, one almost forgets an entire coal mine sits behind the diversion’s massive walls.

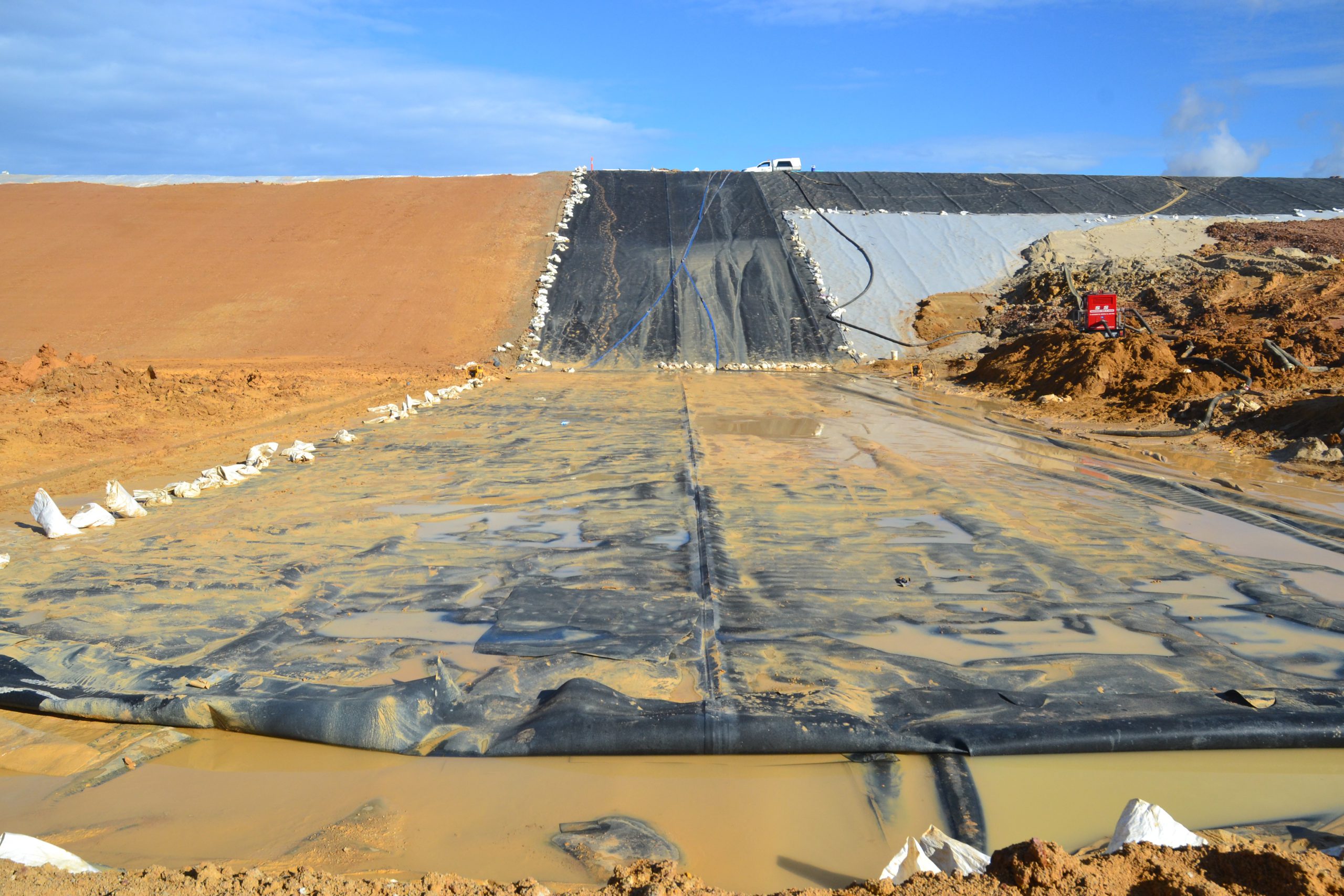

At the northern end, near the levee’s original breach point, a team of workers and excavation equipment work through sticky clay to install an 800 metre liner system – incorporating nine different layers, double seam welded at the joins.

“There’s nowhere for water to go now,” Ron said confidently.

On the day of the tour, the reparation effort was methodical and well organised, however this hasn’t always been the case.

During the initial response period, the mine’s major excavation contractor RTL, with “world class” experience, was scrambled to provide the “emergency coal winning” effort when supplies were under threat.

However no one had ever experienced that much water.

Experts where called into the logistical nightmare from across the country; at the peak of the response, more than 100 workers were dedicated to the reparation.

“Purely getting the amount of pumps we needed in was one of the biggest challenges – to give you an idea, we had 80-odd pumps the size of D10 dozers going at one point,” Ron said.

“Getting all that piping in wasn’t easy either.”

The exact cause of the collapse is still publicly unknown.

While a government investigation is yet to be released, a draft report helped influence the diversion’s redesign.

Of the “half dozen” possible causes identified at the time, Ron said the redesign assumed all were the fault, and were factored in to “ensure nothing was missed”.

After Ron’s “pride” of having spent five years assisting in the $250 million construction of the diversion itself as part of a mine expansion – an achievement which won an engineering excellence award – the river’s collapse was “devastating” and “disappointing”.

The restoration effort has enjoyed favourable working conditions during a long dry summer, however a possible return to Gippsland’s trademark winter rains put the current tentative September completion date under question.

The repair effort was reminded all too well of this last weekend, when a mere 25 millimetres of rain shut down the site for four days.

Is the ambitious pursuit to out-engineer nature asking for trouble?