By Sam Darroch

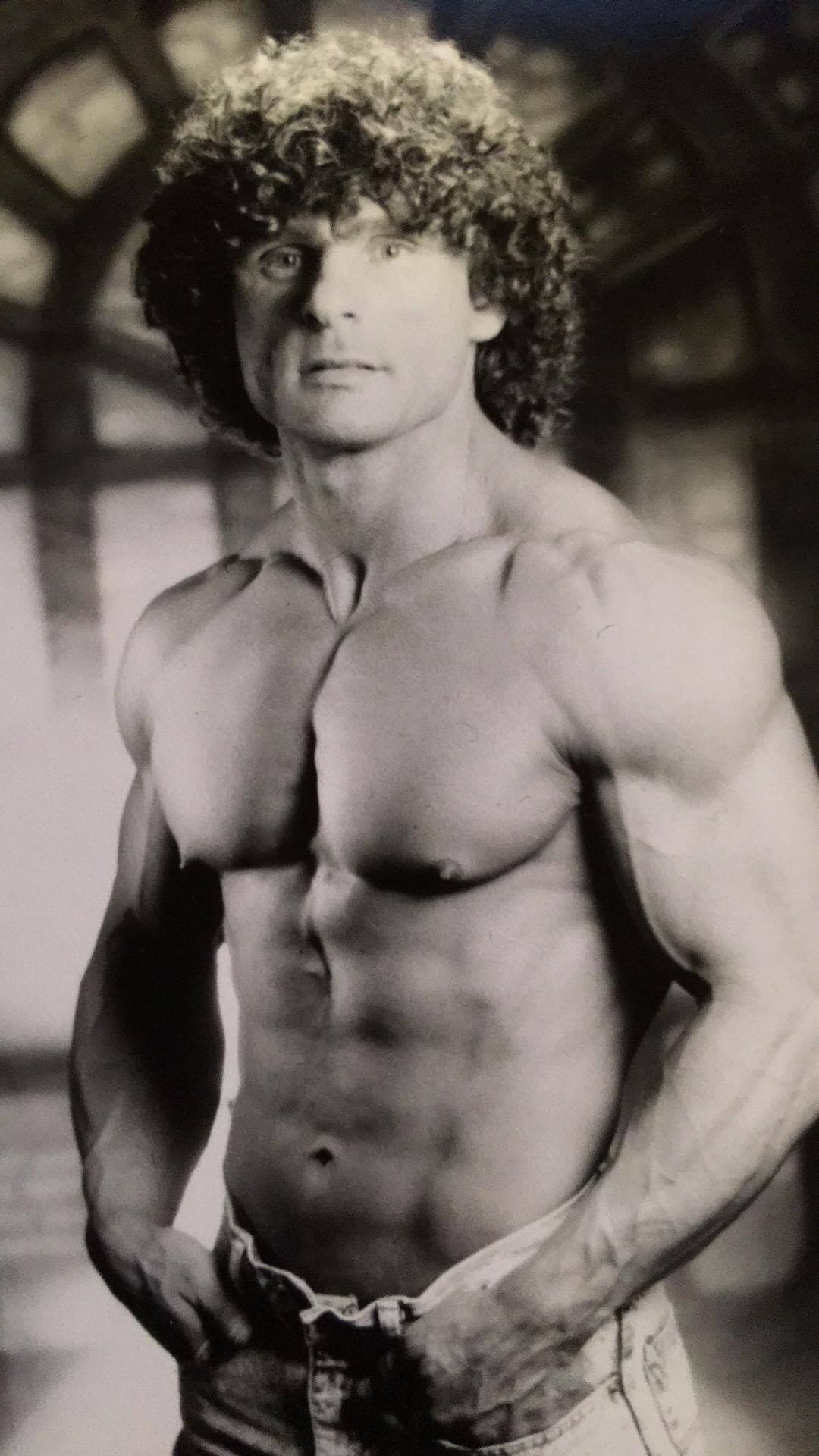

As a bodybuilder Renald Buhagiar was a mountain of muscle, but his strength ran far deeper than the hulking physique that made him Mr Australia.

Bronzed in competition with a heart of gold beating beneath, it was unrivalled strength of mind, body and character which defined the man who became an institution in Gippsland.

On 17 October, 2016, the Latrobe Valley lost one of its favourite sons – a husband, father, friend, competitor, coach and mentor when Renald passed away at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre.

In the end, even cancer couldn’t beat the renowned battler, but a blood clot and collapsed lung were too much for even a fighter of his calibre to overcome.

More than 1000 people attended his funeral late last year and tributes flowed from all comers, recalling a man who touched and changed hundreds of lives.

Tributes and acknowledgements continue; this month Australian soccer star Archie Thompson offered the family his condolences during a visit to the Valley, where the name Renald Buhagiar resonates loudest.

Renald was born on 2 August, 1964.

He lived his early life on a farm and loved fishing, hunting and playing cricket or soccer in the backyard – always day-dreaming he was representing Australia.

A headstrong child, he stubbornly stood by his convictions whether they were right or wrong.

Figuring he would grow up to be a famous athlete and an actor, he didn’t put much stock on education as a youngster, but pursued his sporting endeavours with vigour.

While he never donned the green and gold he did make his mark as a local sportsman.

Few who saw his “jaw-dropping” hip and shoulder to save a North Gippsland football grand final for Gormandale would argue against his quality on the field.

Convinced he wasn’t tall enough for the big leagues, it was as a coach that he truly made his mark – first with Olympians Soccer Club in his hometown of Traralgon and later in life as a personal trainer.

Long after his dreams of becoming a professional athlete had faded, Renald found success in another athletic discipline that would become synonymous with his name ever after.

RENALD’S motivation to try bodybuilding was simple – someone told him he couldn’t do it.

He ultimately proved them wrong, with Mr Victoria and Mr Australia titles in 1999, but success wasn’t immediate.

At about 110 kilograms Renald was a solidly built fellow, and diet proved a struggle for the newcomer.

He experimented with the discipline in his 20s, with mixed results, before one day committing to take it on whole-heartedly.

He would later shred more than 30kg to compete at 79.9kg in the under 80kg category where he made his name.

In 23 years of competition he rarely missed a national event and always did it clean, in terms of diet, exercise and supplements.

While he didn’t win on debut – he made the podium – exposure to the cliques and the politics only motivated him to blaze his own trail.

Renald was fiercely loyal; professionally he was involved in security – a typically fickle industry – but held his clientele for two decades.

His loyalty spanned to patronage of his local gym, but he’d make a point of going to train in Melbourne so his rivals knew who he was, where he was from and what he was about.

One year he came out to compete with the backing track of ‘Mr Natural’ just to “stick it up them” so they knew he wasn’t on any controversial supplements.

He pursued his goals with absolute conviction; when he was competing for Mr Australia one year he knew he might not make the weigh-in and didn’t drink any fluids for 48 hours.

His discipline was unrivalled no matter the circumstance.

When his wife Debbie was having their first child, Jesse, Renald popped open his pre-prepared steamed chicken while she was in labour and was off to the gym following his birth.

His sister Judi said it was a hallmark trait.

“If I said he was committed that’s probably the understatement of the century,” she said.

“He used to always say ‘I’m so dumb’, but in actual fact his strength of mind was, upon reflection, his absolute strength; I’ve never met anyone with that strength of mind.

“I’ve worked with some of the best athletes not only in this country but in this world… I have never ever known anybody to achieve what they’ve achieved through sheer determination, will power, grit and guts.”

WHETHER it was soccer or weights, as a coach Renald aimed to get the best from those he trained.

There were no secrets withheld or sugar coated rhetoric, just an honest and earnest approach to improvement.

Judi recalled a man who, even after he had reached the top of the bodybuilding world, would readily offer his knowledge to anyone who asked, as long as they made a genuine effort.

“He loved imparting knowledge. He wanted everyone to be as good as him; he had no fear of anyone surpassing him,” Judi said.

“There are people out there who would fear their position being taken, he’d relish it. If someone could come along and take that title off him he’d go ‘well done’ and he’d be the first one to shake their hand and say ‘good on you’, but no-one ever did.”

Described as having a shyness or reservedness about him, Judi said Renald didn’t think he had what it took to be a coach or a mentor.

But he had a magnetic quality few could resist.

“As a kid I’m older than him but I would look up to him. I still can never put my finger on it, even before he died I used to always think, ‘what is it about him that makes me want to hang around him?’

“He was funny as a coach, he’d get in trouble all the time because he wore his heart on his sleeve.

“He wasn’t a saint, he just commanded respect from people.”

After his first bout with cancer Renald and Debbie built their dream home, which of course included a standalone gym.

If he wasn’t at Body and Soul, where his former bench became a shrine after he passed, he would be at home helping get people into shape.

“Some of the people who came out here were not going to be bodybuilders… he just wanted to see them improve,” Debbie said.

“He’d give the kids self-confidence. He’s had kids out here that might have been a bit overweight and just to have them get fitter, but more to have the self-confidence to be what they want to be.”

Renald helped train basketballers like Chelsea D’Angelo and Innika Hodgson – and their parents would thank him for his influence getting them where they wanted to go.

“He was so proud for them, not for him,” Debbie said.

The mark he made on young athletes was brought into context when droves of people attended his funeral with similar stories.

Debbie said she had adult men approach her at the funeral saying Renald coached them in under 16s more than 20 years ago and that “he paved the way for who I am today”.

On his 48th birthday Renald found a lump on his neck – it was throat cancer.

In the midst of training for an event he was told by doctors he could compete one last time before treatment, and he’d have to pile on as much weight as possible to prepare for radiation therapy.

Despite struggling to eat, he wouldn’t succumb to having a tube up his nose.

It didn’t matter if it took him two hours to finish his dinner, that’s what he’d do.

After meticulously weighing every meal and eating at the same time every day, it was a big adjustment when he was told by nutritionists to eat whatever he wanted, be it fast food or cookies.

“He just couldn’t get that,” Debbie said.

“He’d say “why would I want to do that? Now I’m not going to die of cancer I’m going to die of blocked arteries.”

As he always had done, Renald fought, battled and braved the hard times to come out the other side.

After being given the all-clear he decided to compete again, despite having lost significant size and strength.

By the end of the year he’d won the Mr Victoria masters and coached his son’s under 12 soccer team to the premiership.

It was business as usual.

And so it went for almost four years until the cancer resurfaced.

While they caught it early, and Renald made the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre a second home, he took a turn one day when a suspected blood clot broke into his lung and it collapsed.

True to form, even while on 100 per cent oxygen support, Renald was talking.

“They said we can’t believe (he was talking) because nobody is able to keep the mask on because it drives them bonkers,” Debbie said.

He showed signs of improvement but eventually died on 17 October, 2016, and disbelief was palpable.

“Only because we know how strong-minded (he was).”

THE weight of tributes that flowed in for Renald on social media after his death spoke volumes about his influence in the community.

He will be remembered as a champion athlete, coach, mentor, friend, husband and father to Jesse, Nikita and Claudia.

“It was more about the life skill he wanted to teach people than how to kick a ball or lift a weight,” Judi said.

“It wasn’t about that. It was believe in yourself, live your life with a true mindset and sincerity for yourself. That was him.

“He wanted you to know he was Mr Australia but he didn’t want that to be the reason for respecting him.

“To us he wasn’t Mr Australia, he was Renald.”

1996 – 2nd place Mr Victoria

1997 – Men’s Novice, Mr Victoria

1998 – 2nd place Mr Victoria

1999 – 1st place Mr Victoria

1999 – 1st place Mr Australia

2003 – 3rd place Mr Australia

2005 – 2nd place Mr Victoria

2010 – 1st place Mr Victoria Masters

2011 – 1st place Mr Victoria Masters

2014 – Finalist Mr Victoria & Mr Australia

2015 – 2nd place Mr Victoria Masters